Bull Markets Usually Don’t End With a Bang

Do you think we’re near the top of a bull market? Join the conversation below.

Of course, there is no way of knowing whether the current stock market—which pulled back brutally from record highs in late September, before Friday’s rally to start October—has entered such an extended topping process. But the bull market will someday come to an end, if it hasn’t already, and it’s important to review the characteristics of past tops so that you don’t manage your portfolio on the assumption that you will be able to catch the top in real time.

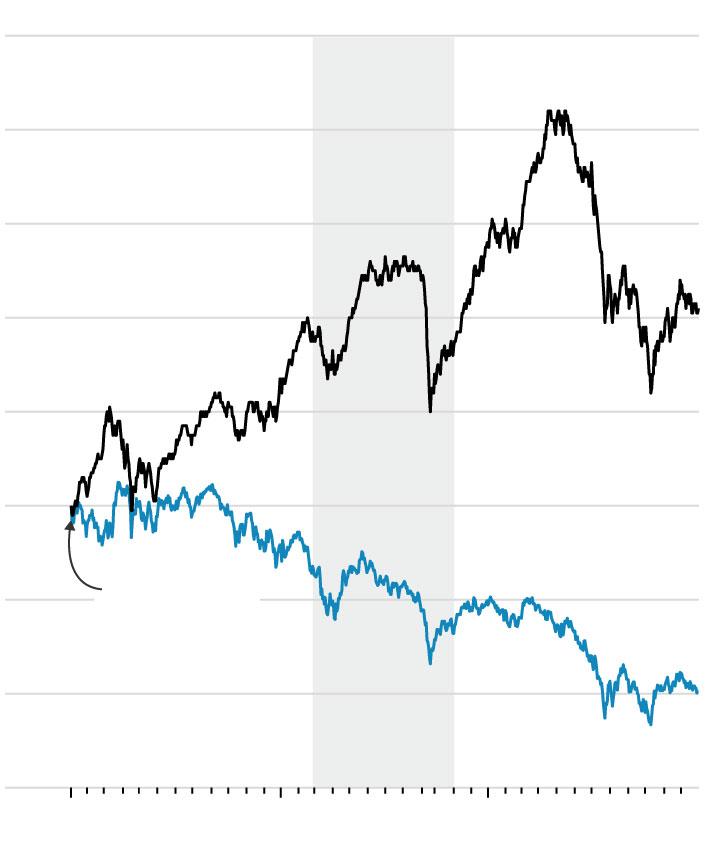

A recent illustration that not all sectors and styles hit their bull-market highs at the same time came at the top of the internet-stock bubble in early 2000. Though the S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite indexes hit their bull-market highs in March 2000, value stocks—and small-cap value stocks, in particular—kept on rising. The S&P 500 at its October 2002 bear-market low was 49% lower than its March 2000 high, and the Nasdaq Composite was 78% lower, but the average small-cap value stock was 2% higher than it was in March 2000, according to data from Dartmouth professorKenneth French.

A look at 30 bull markets

While this is just one example, it isn’t unique. Consider what I found upon analyzing the 30 bull-market tops since the mid-1920s that appear in the calendar maintained by Ned Davis Research. In each case, I determined the dates on which various market sectors hit their particular bull-market highs: the large-, mid- and small-cap sectors, as well as the value, growth and blend styles, as measured by stocks’ price-to-book ratios. Averaging across all 30 bull-market tops, there was a 225-day spread between the earliest date on which any of these sectors hit their tops and the latest. That’s more than seven months.

There are exceptions, especially when an external event causes the market to crash and virtually all sectors drop in unison. The 1987 stock-market crash, as well as the declines in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the March 2020 pandemic lockdowns, are good examples. But in most cases it’s more accurate to view a bull-market top as a process rather than a single event.

Sentiment factor

Another reason to view market tops as a process is that it’s unlikely that, on the day on which broad market indexes such as the S&P 500 hit their bull-market highs, you will have any idea that a bear market is imminent. Instead, you will most likely be caught up in the exuberance of the moment. Only in retrospect will it become clear that a bear market was in the process of starting.

This exuberance leads investors to be too heavily invested in stocks during the latter stages of bull markets. Believing that the exact day of the top hasn’t yet been hit, they hang on to their stock positions for too long. Viewing market tops as a process can counterbalance this exuberance, since it leads investors to focus on their individual positions rather than the market as a monolithic whole.

RECESSION

$200

Small-cap value stocks*

180

160

140

120

100

S&P 500 index

80

1/3/2000 value = $100

60

40

2000

’01

’02

RECESSION

$200

Small-cap value stocks*

180

160

140

120

100

S&P 500 index

80

1/3/2000 value = $100

60

40

2000

’01

’02

RECESSION

$200

Small-cap value stocks*

180

160

140

120

100

S&P 500 index

80

1/3/2000 value = $100

60

40

2000

’01

’02

RECESSION

$200

Small-cap value stocks*

180

160

140

120

100

S&P 500 index

80

1/3/2000 value = $100

60

40

2000

’01

’02

RECESSION

$200

Small-cap value stocks*

180

160

140

120

100

S&P 500 index

80

1/3/2000 value = $100

60

40

2000

’01

’02

*Stocks with below-median market caps and which also are among the 30% with the lowest price-to-book ratios

Sources: Ken French; Hulbert Ratings LLC

Many resist this advice because their memories play tricks on them, leading them to believe it is possible to spot a bull-market top as it is happening. It most definitely isn’t, according to my firm’s day-by-day tracking of the advice of stock-market timers—advisers who tell clients how much of their investment portfolios should be in equities and how much in cash. On those days over the last four decades in which the S&P 500 hit a bull-market high, these timers’ average recommended equity exposure level was 65.7%. That’s a higher exposure level than on 95% of all other days over the past 40 years.

On those days when the S&P 500 hit its bear-market lows, in contrast, stock-market timers’ average recommended exposure level was just 5%.

2007 memories

Think back to October 2007. Even though the S&P 500 was about to embark on a 16-month decline of 57%, virtually none of the approximately 100 stock-market timers that my firm monitors were envisioning anything of the sort.

This failure was true even for those market timers with the best long-term records coming into that month. One of the top long-term performers at the time was telling clients that a bear market was such a remote possibility that it wasn’t even on his radar screen. Another moved from being fully invested to going 25% on margin—borrowing to invest even more in stocks—the day before the exact day of the S&P 500’s bull-market high.

If these market professionals with good long-term records weren’t able to anticipate the beginning of one of the most serious bear markets in U.S. history, you’re kidding yourself if you think you can consistently do any better. You’re more likely to be successful by viewing the end of a bull market and the beginning of a bear market as a process rather than a single event.

Mr. Hulbert is a columnist whose Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at reports@wsj.com.