New insights on commemoration of the dead through mortuary and architectural use of pigments at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey

The use of pigments by past societies has been considered as evidence for modern human behaviour based on its association with symbolic activities and rituals1,2,3,4. Middle Stone Age sites younger than 180 kya in Africa3,5,6,7,8,9and the Middle East10,11,12show systematic evidence of red pigment use. In mortuary contexts, pigments became prevalent during the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe13,14,15,16,17, but in the Upper Palaeolithic Near-East, the number of recovered burials remains relatively small18,19, as is the evidence for ochre processing and ochre use18,19,20,21.

The earliest Near Eastern case of pigment use in an architectural context dates back to the Early Natufian period with a building coated with plaster and red paint from the site of Ain Mallaha-Eynan22. Also attributed to Natufian traditions is the origin of complex manipulations of skeletal elements such as the removal, modelling and painting of crania23,24, although evidence for funerary pigments remains limited to only a few sites; Azraq 1824, Ain Mallaha-Eynan25and Hayonim cave26. In the early Pre-Pottery Neolithic period (PPNA) both architectural and funerary evidence of pigments continues to remain scarce. The sites of Dja’de el-Mughara and Mureybet, located along the Syrian Euphrates (northern Levant), show evidence of architectural paintings during different Pre-Pottery Neolithic phases with emerging variation in mortuary practices, limited pigment applications and secondary deposits in clear connection with the architecture25,27,28,29,30,31. It is only during the second half of the 9thmillennium and the 8thmillennium BC that architectural paintings and funerary pigment use seem to spread across a large area reaching from the Southern Levant to Central Anatolia25,32. Increasingly common examples of secondary handling of human remains in single or collective burials, removal of crania and the presence of elaborate burial associations signal selection and increased symbolism that continued through the Neolithic24,33,34,35,36.

Focussing on Anatolia specifically, changes in mortuary practices were accompanied by a growing variability in pigment processing and application. The Epipalaeolithic levels of Pınarbaşı show evidence of ochre processing as well as the presence of colourants in a burial context37,38. The Early Neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe, known for its architectural decorations of stone carvings and bas reliefs, provided cranial fragments with traces of red ochre but was lacking burials39. Near the northern extension of the Fertile Crescent, black and red pigments were observed on bones recovered at the Early Neolithic sites of Körtik Tepe, Demirköy and Hasankeyf Höyük40,41,42. Several phases from Çayönü revealed buildings with red paint and ‘skull buildings’, but without reported pigment on human remains43,44. In Central Anatolia, red paint was found on walls, floors and benches in ‘special’ or communal buildings at Aşıklı Höyük45. In contrast, ochre in burials and on ornaments was rare and traces were only found on one bead, one shell and in the burials of two children and one adult female46,47,48. At the site of Musular, red pigment was observed on floors and benches, but not reported on human remains49. In Boncuklu Höyük, red colourants were attested on walls and floors, as well as in burials; occasionally on crania and with secondary/tertiary depositions of human remains50,51,52. The late Neolithic phases of Köşk Höyük revealed a wall painting32,53and 13 out of 19 plastered human crania were covered with red ochre54,55. The site of Tepecik-Çiftlik has one architectural feature with red and blue colourants in a building dated to the final Neolithic period32, but no pigments were reported on any of the more than 170 human remains56,57.

These examples suggest important symbolic, ritual and social behaviour in the Anatolian Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic periods. Repetitive use of imagery, secondary mortuary treatments and increased circulation of human bones highlight integrated systems of social memory by linking the living to the dead and, thus, creating the basis for social differentiation58,59,60. A problem raised in the past, however, is that many discussions focus on post-mortem skull removal while other factors central to mortuary practices remain under-explored, such as associations between burial contexts and architectural features61. The fact that archaeological contexts of paintings and burials are not physically connected is often a reason to ignore correlations between the two, despite ethnographic examples demonstrating the overlap between domestic and ritual practice60,62,63,64,65,66,67. The lack of analyses linking the dead, the physical space of the house and colourant use has been raised about Çatalhöyük specifically62,68,69, but no attempt has been made so far to fill this gap. The long-running, 25-year excavation project at Çatalhöyük provides the opportunity to compare the use of colourants in architectural and funerary contexts in several buildings from successive periods in order to discuss the possible social relevance and symbolic meaning of pigments within this Neolithic society.

Çatalhöyük is one of the largest Neolithic settlements in Anatolia35,70. Archaeological excavations of the site took place between 1961 and 1965 under the direction of James Mellaart, and from 1993 to 2017 by Ian Hodder71. The Neolithic occupation on the East Mound at Çatalhöyük can be placed between 7100 cal BC and 5950 cal BC72, a timeframe encompassing the Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B and the beginning of the Pottery Neolithic.

The Neolithic occupation of Çatalhöyük is subdivided into four phases according to stratigraphic, radiocarbon, archaeological and anthropological data72,73,74,75. These phases pinpoint important cultural and demographic changes. Between the Early (7100–6700 cal BC) and the Middle occupation periods (6700–6500 cal BC) the population gradually rose, houses became larger and symbolic elaboration at the site increased74,75. During the Late (6500–6300 cal BC) and Final (6300–5950 cal BC) occupation periods households became more autonomous75,76. From 6500 cal BC until the abandonment of the East Mound available data suggest greater mobility of the population, economic independence among households, and increased specialisation and differentiation74,75. The same traits are shared with the later cultural and socio-economic development during the Chalcolithic between the East Mound and neighbouring West Mound74,75,76.

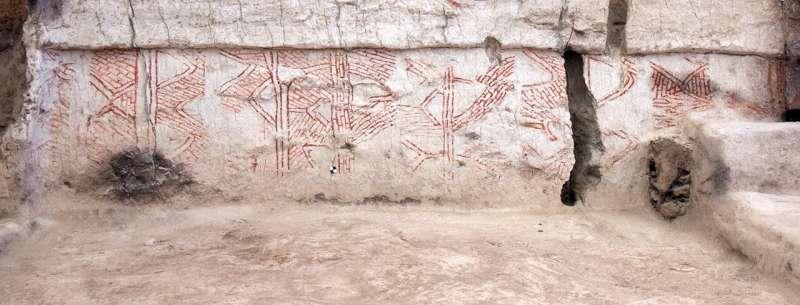

The excavation of Neolithic Çatalhöyük has produced an important number of primary and secondary depositions. Burials mostly occurred within domestic structures during the occupation phase of houses and for a minority in construction and abandonment phases of the buildings77. Adults were most often placed in a flexed position, located beneath the northern and eastern platforms of the central room. Perinate, neonate and infants were buried in more variable locations within the house77,78,79,80. In the Final period, the houses no longer accommodate distinct platforms with burials74and there is an increase in the ratio of secondary to primary depositions77. A well-known feature at Çatalhöyük is the presence of pigments in both funerary and architectural contexts. Although the use of pigments is recognised as one of the defining elements of this community, previous research has focused mainly on one aspect (presence in architectural contexts) of its variability32,68,81,82,83.

This study provides, for the first time, a fine-grained quantitative analysis of the available funerary and architectural data related to pigment use at Neolithic Çatalhöyük. By means of a joint study of different datasets, until recently considered in isolation from each other, the aim is to offer a new perspectives on the possible social processes involved in the use of pigments in this society. To do this, the following research questions are addressed: (a) Which pigments were used at Neolithic Çatalhöyük and in which relative frequency? (b) In which manner were pigments deposited in funerary contexts? (c) What are the associations between pigment use, type of deposition, and sex and age-at-death of the deceased? (d) Is there a chronological variability in the association between architectural use of colourants and mortuary patterns?