Punning, Toileting, and Purifying: the Awakening of Rújìng

An earlier version of this post has been up awhile at my Patreon page, and I’m now posting publicly. Click here to learn more about Patreon and to support my teaching practice.

“Punning…” is part of a series in which I’m highlighting the backgrounds and teachings of several ancestors in the Cáodòng/Sōtō lineage before and after Dōgen. I’m doing this in order to explode the myth about Dōgen, current in much of Sōtō Zen, that Dōgen and his crew were “just sitters” who weren’t into awakening and didn’t use kōans for anything but intellectual off gassing. The truth is au contraire.

Granted, my efforts are less like dynamite and more like the slow drip of the kitchen faucet. In any case, you might wonder, why do I care?

Denying the power of kōan and diminishing the significance of kenshō discourages people from doing the work necessary to awaken into one of the most wonderful and meaningful experiences of this human life. It also diminishes the power and possibility for practicing awakening, liberating living beings.

Meanwhile, Dōgen saw himself as teaching within the context of buddhas and ancestors, not as a rogue monk making shit up. How do we know this? For one thing, in his Shobogenzo and Eihei koroku Dōgen uses the phrase “buddhas and ancestors” about 150 times, often beginning Shobogenzo fascicles with some reference to buddhas and ancestors, setting what he’s about to say in the context of, yes, buddhas and ancestors.

Oh, by the way, Dōgen uses shikantaza nine times in Shobogenzo and Eiheikoroku, but not as a technique – as a keyword. So at least by word count, buddhas and ancestors were 16.66 times more important to Dōgen than shikantaza.

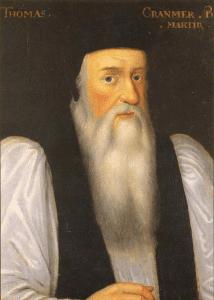

So in this series, you’ll find recent posts on Koun Ejō and Keizan Jōkin. Before attending to Tetsu Gikai, the third generation in Japan, I’ll first offer several posts about the Chinese master, Tiāntóng Rújìng (天童如淨; Heavenly Child Pure Suchness; J. Tendō Nyojō; 1163–1228). This post is about Rújìng’s awakening experience with his teacher, Xuědòu Zhìjiàn (雪竇智鑑; Snow Hermitage Wisdom Mirror; J. Setchō Chikan; 1105–1192). (1)

Rújìng became a monk at an early age and travelled widely, tirelessly seeking the great truth of the buddhadharma. In the Denkōroku (伝光録, Record of the Transmission of Illumination), Keizan Jokin (瑩山紹瑾, Lustrous Mountain Bequeathing Jewels, 1268–1325) says that “From the age of nineteen he [Rújìng] abandoned the study of teachings and sought instruction from holders of the ancestral seat.”(2)

In so doing, Rújìng trained with teachers in the Chán lineages still active in China – the Línjì, Cáodòng, and probably also the Yúnmén teachers. Later in life, Rújìng himself became a renowned teacher, leading several of the premier Chán monasteries. During his installation ceremonies, he defied the tradition of offering incense and dedicating it to his transmission teacher, that is, indicating from whom he had received transmission, and in so doing, identifying which lineage he represented. In other words, he didn’t reveal his lineage publicly until close to his death.

Just before his death, Rújìng shared that Xuědòu Zhìjiàn, a Cáodòng lineage master, was the teacher from whom he’d received transmission and whose lineage he transmitted. Presumably, then, the young Dōgen also would not have known the lineage in which he was undergoing training.

Given that while Rújìng was teaching no one knew what lineage he represented, students would have selected him as their teacher only knowing that he taught from the ancestral seat as a Chán master (otherwise Rújìng couldn’t have become the abbot of any of the several large state-sponsored monastery he taught at). Apparently and importantly, students also could not discern his lineage affiliation based on his practice or teaching.

Rújìng’s wholehearted practice and vigorous teaching represented the One School Zen, as I think you’ll see if you stick with this series. Rújìng’s One School Zen was clearly the source for how Dōgen focussed only on the buddhadharma, not even pledging allegiance to “Zen.”

This is the vital spirit of Zen, free from the political and ideological shackles of our Japanese lineage’s recent history, and focussed just on the buddhadharma (while holding our own lineage ancestry close to our hearts), that I put forward and call “One School Zen.”

Now let’s get to Rújìng’s awakening (悟, “satori,” is used in the Denkoroku).

After Rújìng had trained for a while with Xuědòu, and maybe after an initial awakening (see below), Rújìng came to Xuědòu with what might seem to be an unusual request. Rújìng, you see, asked to be promoted to Toilet Manager. Even though I was nicknamed “Golden Samu Number One Shit Carrying Monk,” at Bukkokuji (true story), I never asked to be the Toilet Manager. How about you?

In a note to his Denkoroku translation, Bodiford explains, “This was a position of some importance in the bureaucracy of large Buddhist monasteries in Song China, where the number of residents could reach one or two thousand. The main duty of the manager was to oversee the emptying of toilet pots and the routine cleaning of the facilities.”

Patti Smith would not be surprised. She sings (well, these lyrics are in a song but she speaks them),

“The transformation of waste is perhaps the oldest preoccupation of man/man being the chosen alloy, he must be reconnected via shit, at all cost/inherent within us is the dream of the task of the alchemist/to create from the clay of man/and recreate from excretion of man pure and then soft and then golden.”(3)

The transformation of waste, indeed. Pure, soft, golden.

When Rújìng asked to be the Toilet Manager, Xuědòu said that if he could answer one question, he’d make that appointment. Now that might seem shitty, but not yet punny, so hang on and I’ll get to the punny part.

Xuědòu’s one question was, “Like how can you purify that which has never been defiled?”

In Chinese, when Xuědòu said, “Like how can you purify…,” the words he spoke would have been “Rúhé jìng dé.” You will notice that there’s a “Rú” 如 and a “jìng” 淨 in that phrase. Yes, the pronunciation (and characters) for Rújìng’s name, which could be translated as “Like Clean,” or “Like Purity.”

And although the framing here is a general question, it could also understood as a personal question, “How has Rújìng never been defiled?” And/or as a statement: “Like purity (Rújìng) has never been defiled.”

It all gets down to “show me that which has never been defiled.”

Beyond the pun, one definitely needs to go into the shit to realize that one. I’m afraid, though, that explaining the pun took the fun out of it for ya! Sorry about that. If it did, though, there’s still Patti’s accidental commentary. Xuědòu knew that Rújìng “…must be reconnected via shit, at all costs.”

And so he was. The story has it that Rújìng met with his teacher repeatedly, trying to answer this question, but when asked, “Like how can you purify that which has never been defiled?” he had no words. This went on for more than a year, then suddenly he clearly did satori, and said, “Hit undefiled place!”

In Denkoroku, Keizan says that “… Before he was done uttering that [“Hit undefiled place!”], Xuedou hit him. The Master [Rújìng], sweat pouring, made prostrations. Xuedou thereupon gave his approval.”

This awakening story is very much like that of Rújìng’s younger contemporary Xūtáng Zhìyú (虚堂智愚, 1185–1269) with his Línjì lineage master, Yùnān Pǔyán (運庵普巖, 1156–1226). Although there’s no pun or Patti Smith song that goes with Xūtáng’s satori. There is a book, though: The Record of Empty Hall.

Rújìng’s awakening lit up the house of One School Zen.

As noted above, this account of Rújìng’s awakening occurs in the Japanese Sōtō master Keizan’s Denkōroku.

Bodiford notes, that it “… has no precedent in extant Chinese sources. However, there are several Chinese records that give an entirely different account. For example, the biography of ‘Chan Master Changweng Rujing of Tiantong in Mingzhou’ says: [Rujing] sought instruction from Zhijian at [Mount] Xuedou and gained insight while contemplating the words ‘cypress in the garden.’ This other account agrees with the Denkōroku, however, that Rujing’s awakening came through the practice of “contemplating” (C. kan 看; J. kan) the “words” (C. hua 話; J. wa) of a kōan: ‘Zhaozhou’s cypress in the garden.’”

The biography of Rújìng’s that has him awakening through contemplating “Zhàozhōu’s Cypress in the Garden” is “Five Lamps Merged at the Source” – think “One School Zen.”

To complicate matters further, “The Record of Rújìng,” has Rújìng realizing great awakening through the kōan, “The World Honored One’s Secret Saying.” See Ruijing and Six Intimate Dharma Heirs for more.

As for the controversy about Rújìng’s awakening, it isn’t about whether Rújìng had a definitive awakening or not, or whether it came from contemplating words (看話, J. kanwa) of a kōan or not, but which kōan words he was contemplating. Incidentally, all three versions agree that his awakening came with the Cáodòng master, Xuědòu Zhìjiàn.

How do I explain these three different awakening stories?

Scratching my head, I come up with a few possibilities. First, because awakening is often not one and done, it is possible that Rújìng had an early awakening while contemplating the words of “The World Honored One’s Secret Saying” another with “Zhàozhōu’s Cypress in the Garden” and then a later awakening with “Like how can you purify that which has never been defiled?” Or some other order.

This possibility relies on Keizan having access to information about Rújìng’s awakening through means other than extant Chinese sources. For example, Keizan could have learned about Rújìng’s awakening from Chinese sources not available today (Keizan blocked the text as if he was quoting sources the same way he did for other ancestors) and/or verbally through Dōgen, Ejō, or Jakuen (a Chinese monk and student of Rújìng who followed Dōgen back to Japan and later was one of Keizan’s teachers).

Given that the volume of “The Record of Rújìng” where “The World Honored One’s Secret Saying” version comes up is attributed to Dōgen himself, that might lend this version some credence, although not necessarily as Rújìng’s only awakening.

At the same time, it is notable that a contemporary of Rújìng, Cáodòng master Shèngmò (勝默, n.d.), also used the “Zhàozhōu’s Cypress in the Garden”as a breakthrough kōan. In his The Record of Going Easy (從容錄, Cóngróng lù; J. Shōyōroku), Cáodòng master Wànsōng (萬松, 1166–1246) notes that his former teacher “… Shengmo had people pass through this case first, cleansing prior knowledge.” That might lend credence to the “Zhàozhōu’s Cypress in the Garden” version, but, again, not necessarily as Rújìng’s only awakening.

Another possibility is that the storytellers of the various awakening experiences got confused and whose awakening went with which teacher got tangled.

In any case, it’s all a story.

So more One School Zen.

Rújìng awakened through contemplating the words of a punny, personal, and impromptu kōan given to him by Xuědòu Zhìjiàn. At least, that’s one version of his awakening. In any case, Rújìng’s process is much like that of many of those who’ve awakened, at least during the past fifteen hundred years. Rújìng’s teaching had it’s own particular flavor, but not a flavor that would align it with any one lineage or another.

Indeed, Rújìng went to considerable lengths to hide his lineage affiliation until the end of his life, an effort that was apparently successful. In 13th Century Chán/Zen, there really wasn’t much (if any) difference between what became Japanese Sōtō and Rinzai. Both lineages stressed awakening, as any school within the framework of Mahayana Buddhism would do. Both used kōan to catalyze awakening. After all, kōan introspection is the best idea since the Buddha’s time, so why not embrace the koan methodology? Differences in approach to kōan depended more on a specific teacher’s proclivities and creativity and much less on the teacher’s lineage.

I’ll soon be advancing a theory for why Cáodòng/Sōtō and Línjì/Rinzai lineages were so much alike in the 13th century, but meanwhile, I’ll just say this: Rújìng was one fine example of One School Zen.

Finally, the story that Dōgen inherited a brand of Zen that used a special meditation technique, shikantaza, that sitting itself was awakening, that his lineage rejected kōan work, that this special transmission denied the importance of personal awakening, and instead stressed original awakening is one big myth. The source of this myth goes back only about 150 years or so to those who rebranded Sōtō Zen to comply with the Meiji government and to compete with Christianity. See The Showa Dispute about True Faith for more.

This myth is killing Sōtō Zen in Japan and it will kill Sōtō Zen in the global culture – if it remains as the dominant narrative. See The End of Zen in Japan? for more.

(1) This was not Xuedou Chongxian (雪竇重顯, 980–1052), the Yunmen lineage master who compiled the cases and wrote verses for what became The Blue Cliff Record.

(2) For all references in this post to Denkoroku, see Record of the Transmission of Illumination, by Keizan Jokin, trans. William Bodiford. I’ve retranslated the main case, though, so that it more clearly plays with the pun:

The Fiftieth Ancestor, Tiāntóng [Rú] Jìng Oshō consulted Xuědòu. Dòu asked Jìng, “Like how can you purify that which has never been defiled?” The master passed through more than one year, then suddenly clearly awakened (悟, satori), and said, “Hit undefiled place!”

(3) See https://youtu.be/faQjQjhtino

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri.